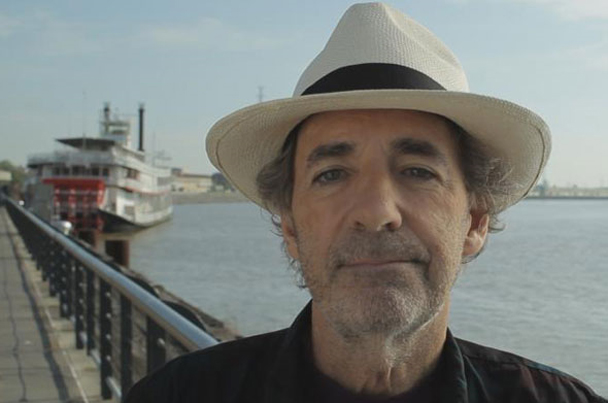

Harry Shearer

The man formerly known as Ned Flanders, Mr Burns and Derek Smalls about his new film The Big Uneasy

What do you get when you cross an evil nuclear tycoon, a heavy metal bassist, a radio presenter, a political science graduate, a moustachioed Christian neighbour, a campaigner, a Saturday Night Live writer and the flooding of 80% of New Orleans?

Harry Shearer, of course. The legendary actor, writer, comedian and voice of The Simpsons is currently promoting his new documentary The Big Uneasy. As the title may suggest, Shearer’s film thoroughly dismantles the myth that Hurricane Katrina was an ‘unprecedented natural disaster’, and instead shows the uncomfortable truth that citizens of New Orleans were in fact victims of long-term engineering failures and neglect across the city’s infrastructure. The levees broke – flooding the majority of the city – not purely because of Hurricane Katrina; they broke because they were built on sand.

So, how easy is it for a man more commonly known for trilling ‘indeedely doodley’ and sniffing the glove to make the transition in to documentary provocateur?

“It’s complicated,” says Shearer, speaking to me on the phone the morning after a special screening at the Soho Curzon. “Because this isn’t really part of my career, you know. I’m a comedian. What I’ll be really proud of is when the film reaches the people who can really make a difference to New Orleans.” Those who have watched The Big Uneasy will take this as a reference to the US Army Corps of Engineers, an “almost impermeable institution,” who are blamed for a catalogue of long-running, expensive and lethal engineering errors across America.

“What would give me the greatest sense of pride would be if I saw them really attacking me in public,” says Shearer. Such a public confrontation, he suggests, would show that his comments had riled. Otherwise the Corps will merely retreat to their default position that “everything is fine”.

So, while this is in many ways a provocative documentary – in which Shearer takes on an American colossus, and exposes a number of cases in which whistleblowers have been discredited, threatened and even sacked – he is not simply ‘doing a Michael Moore.’ This is instead a film that Shearer felt impelled to make after following the story, and the creation of the ‘natural disaster’ myth, on international news.

“I mean, I’m not an expert here. I don’t really know all this stuff. My job, as I saw it, was to gather and assemble the people who really knew what they were talking about and give them this opportunity to put forward their argument. There are no conclusions of mine in the film.”

Indeed, Shearer wasn’t even in the initial cut of the film, fearing that his presence would make audiences think, “Why am I watching some guy from the Simpsons telling me about this stuff?” And although Shearer is on screen in the final edit, he acts more like the Chorus in a Greek Tragedy, than a traditional documentary maker; a sort of world-weary, cynical commentator who can merely explain the injustices around him, without offering a solution. So, was he surprised to be attacked as ‘naïve’ by John Landis during that Soho screening?

“Well look, I know John,” answers Shearer. “And although that might seem like an attack over here, actually that’s just John clearing his throat. He’s a staunch liberal democrat and so that’s the position that he’s coming to the film from. Like I think I said last night, since making this film, my view of human nature has got a little bit darker, which I didn’t even think was possible.”

A pessimistic Ned Flanders? This is like hearing that Bambi has developed a crystal meth dependency or that Baloo the bear has had to go on Prozac.

“I guess I used to have a lingering sense of the things I rooted for,” explains Shearer. “Like, when Rupert Murdoch attacks the BBC I would usually have been on the BBC’s side. Although I’m less inclined to these days after the way I was treated by Radio 4.”

I interrupt to ask if he is referring to an evil BBC plot to force him to interview his ex-girlfriend Ruby Wax for the Radio 4 comedy programme Chain Reaction. “Oh no. I recorded that in the Spring, but they only broadcast it now. And because they broadcast that, they’re not going to give any more coverage to me or my film.”

However, John Landis wasn’t attacking Shearer for being naïve in his approach to film promotion; the thrust of his argument seemed to be that Shearer was unfairly blaming Obama for a crisis that took root long before his administration, and for ignoring the famously high levels of corruption in New Orleans.

“With Obama, no-one is ever going to take away his achievement,’ explains Shearer. “He was the first president to cross the colour line. But I think his inaction towards New Orleans since he’s been in government is really inexcusable.” Shearer also rebuffed Landis’ corruption argument by pointing out the more recent transgressions by senators of Illinois.

This kind of overt political discussion is something that many Hollywood artists steer clear of, for fear of career repercussions. Is this something that political science graduate ever worried about?

“There’s politics in every part of life,” says Shearer. “I think that the problem with issues like [the flooding of New Orleans] is that when both parties are complicit in the failures, no-one can achieve anything by bringing it up. So it gets swept under the carpet.” So, if an institutional failure can’t be used as a stick with which to beat your opponent then it gets ignored by party politics, leaving it to outsiders like Shearer to pick up the slack.

In other interviews Shearer has stated that “the iron law of doing comedy about politics is you make fun of whoever is running the place.” But while The Big Uneasy is happy to challenge members of the US Army Engineering Corps and the administration alike, it could strictly not be described as a comedy.

“Another iron law of satire is that the audience has to know the same facts as you do,” says Shearer. “So, before I could satirise the situation – which I don’t think I would want to do – I had to inform people about it. I came to this as a layperson, which was useful when it came to presenting it to other laypeople”

One of the few intentionally funny bits that Shearer added to the film is a final screen, which just flashes up the text, “Sent from my iPhone.” Could such a film have been made without the internet?

“The main difference is that the internet allowed me to find a lot of the clips used in the film,” explains Shearer, who worked alongside a team of researchers to collate useful footage. For instance, there is a clip early on in the film in which a leading hurricane expert says, on film, that Hurricane Katrina was ‘category one or category two, at most.’ A category two hurricane could not, alone, cause the level of damage to which New Orleans was subjected. Which rather undermines the Corp’s explanation that this was an unprecedented natural disaster against which it would have been impossible to protect the city.

The internet also allowed Shearer to track down Karen Durham-Aguilera, the civilian head of the Engineering Corps’ reconstruction project in New Orleans; a woman who comes across in the film as so insincere as to be actually unsettling. According to Shearer, Durham-Aguilera is “very little written about” but is key in unravelling the whole shrouded case of the Corps’ responsibility. “The Corps like to put out the guys in military uniform. Because it automatically commands some sense of authority and respect. Well, in our animal brains, anyway. But those men in uniforms tend to spend just eighteen months per assignment, so their default position is ‘well, that was before my time.’ Whereas Durham-Aguilera has been involved for much longer and has a much greater sway.”

The internet aside, another great technological benefit to the film was the Avid editing system, which allowed the team to search footage for key words and quotes, saving “a colossal amount of time.” Time, which they didn’t really have, as the film had to be finished to the deadline of the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, while Shearer was simultaneously presenting his radio programme Le Show, musical projects with his wife the singer/songwriter Judith Owen and, of course, his voiceover work on The Simpsons. “We didn’t have the time and we didn’t have the money,” explains Shearer, and yet the project managed to get completed. How, you may ask? Well, Spinal Tap was filmed in twenty five days; The Big Uneasy in just twenty one.

Since that first US-wide screening of The Big Uneasy on the 30 August, the film has been shown continuously in cinemas in New Orleans. How does Shearer, a self-proclaimed part-time resident, feel about the city?

“The thing about New Orleans is that it’s been around for nearly 300 years. And in that time it has faced a lot of shit,” says Shearer. “There is a philosophy of ‘this could all be over so enjoy it today,’ which sort of colours the whole attitude of the place. As a city, the rules are exactly the opposite of New York City; you say hello to people in the street, you enjoy conversations with your neighbours. But each conversation is filled with the kind of mordant humour of the place. And with each person you talk to, you don’t know if playing in their head is a tape of their mom or dad drowning in the attic.”

COMMENTS