Errol Morris

Something You Should Know Before Seeing The Unknown Known

In this era—thank you Fox News, thank you Rush Limbaugh—where vitriol supplants discussion, where bombast and partisan opinion quashes reason, Errol Morris’s new film has ignited some low-wattage controversy. The Unknown Known is a bloodless portrait of former U.S. Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld, an exposé only in a laissez-faire sense; unlike The Fog of War, Morris’ other documentary on a former Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara, which was a Greek tragedy of hubris and self-excoriation, with a sort of sad happy ending where McNamara is haunted with regret. In The Unknown Known there is no Bill O’Reilly pugnacity, shouting at his subject, calling him a dirty traitor and shutting off his mic, or no Michael Moore (the Left’s equivalent of Bill O’Reilly, thank God for it) making his subject into a buffoon. Why did Morris not call Rumsfeld out? Castigate him for his lies and bullying? Question his anti-matter heart? Why did he let that sad little lizard walk away unscathed? He didn’t, as he himself explains—droll, ironic, as slow and fatal as a crocodile—during a Q & A after a recent screening at the ICA in London. He let Rumsfeld’s own words commit a fine act of self-immolation; it was karma by documentary.

How did the movie come about?

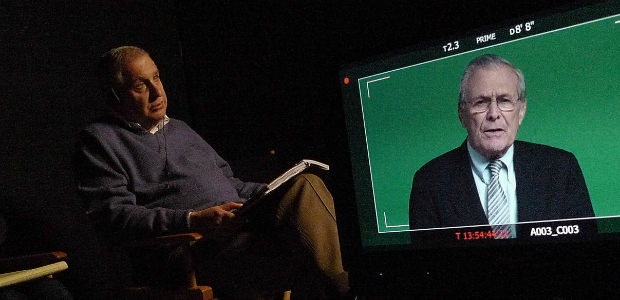

Errol Morris: Standard Operating Procedure was the movie that I made about Abu Ghraib with many of the soldiers who took the infamous photographs in 2003, and Rumsfeld was always a shadowy figure in that story. Also, I had made a movie about another Secretary of Defense who presided over another disastrous war—tidy bookends, if you like—Iraq and Vietnam; there were many reasons to make this film. I was fascinated by the ‘snowflakes’ [how Rumsfeld referred to the blizzard of memos he sent to his staff], Rumsfeld had published a memoir, The Known and the Unknown, a brick of a book—what did Mark Twain call the Book of Mormon? He called it ‘Literary chloroform.’ Not an easy book to read. But the snowflakes, which were not available to the public, the idea of the snowflakes, fascinated me. To me, it was kind of fable, the man who memorializes everything, and yet memorializes nothing. And it seemed, if you’re of my persuasion and you’re interested in telling a story about how people see the world, if you like history inside out, there’s not 10, 15, 20 people telling you what to think about Donald Rumsfeld: there’s Donald Rumsfeld writing about Donald Rumsfeld, there’s Donald Rumsfeld telling you what to think about Donald Rumsfeld, there’s Donald Rumsfeld trying to convince other people how to see him, and so on and so forth. That does interest me, still interests me, even though I find the movie that came out of all this somewhat horrific.

Was the movie difficult to make?

They’re all difficult to make. None of them are easy.

But this one particularly?

Yes and no. On one level, not difficult at all. He was forthcoming, he came to where I live, I didn’t have to go to Washington or to New Mexico. He flew up to Boston, all the interviews were done in a studio in Boston. He supplied the memos, he gave me complete access to the declassified memos, he read them for camera. He was completely cooperative in many, many, many ways. But, in the end, interviewing him was torture. Yeah. We used to talk about, in the editing room, ‘What if he sends me to a black site? What if I end up in one of the stands with someone pulling out my fingernails?’ And then I had this sudden realization that he had turned my office into a black site; I was actually trapped with Rumsfeld for over a year.

Was Rumsfeld genuinely delusory, or was he just determined to rewrite history in his own way?

It’s one of the questions at the centre of every film I’ve ever made. It’s certainly at the centre of this film. Is he hiding something? Is he playing with me? Or is there really nothing there? There is the satisfaction in the Wizard of Oz when they lift the curtain and there’s this little guy pulling the strings, but there isn’t even that satisfaction here. Often it seemed like an excursion to nowhere. I got into a fight at the last screening. And the fight was that somehow I did not do a good enough job in ferreting out something that Rumsfeld was clearly hiding. Aside from the fact that someone is saying, ‘You did a bad job,’ which is never pleasant even in the best of circumstances, I—self-serving of me to say—did not feel I did a bad job. I did something very similar to what I’ve done in almost every single film I’ve ever made, why should I stop with this one? It’s the idea that if you let someone talk, they’re going to reveal something about themselves. And to me it happens again and again and again and again and again in The Unknown Known, it’s just that what you discover is so distressing and horrific—almost counter-intuitive—it’s hard to know what to make of it. It goes to the question of sincerity as well. Someone asked me, ‘Do you think he’s insincere?’ and I said it would be much better if he was insincere. I think he is sincere and that’s what’s truly horrific here. When I ask him, ‘What did you learn about the war, the debacle in Vietnam, close to sixty thousand Americans dead not to mention the millions of Vietnamese?’ he says, ‘Some things work out and some things don’t.’ Ask yourself, what’s been hidden there? I think something’s been revealed. But what’s being revealed is such an amazing lack of depth, such a lack of interest in the world, such a level of self-absorption and self-satisfaction. To me the finest thing I’ve done is the smile. My wife calls him the Cheshire Cat. What does Alice say in Alice In Wonderland? She says, ‘I’ve often seen a cat without a grin, but I’ve never seen a grin without a cat.’ It’s this look of supreme self-satisfaction and it seems often inappropriate. I think amazing things are revealed about Rumsfeld in this movie, it’s just they’re truly depressing. He’s never read the torture memos? Is he lying? It would be great if he were lying! And I don’t think he is. He didn’t care to read them. ‘Why would I read that kind of thing? I’m not a lawyer!’ He’s willing to say anything, clearly, and even if contradicted, which I often do throughout the film, it has no effect. And if you think about his whole ideology, it’s like a return to the dark ages. Evidence doesn’t count for anything, might makes right, weakness is provocative; it’s crazy. It’s deeply, deeply vapid and crazy.

You don’t aggressively confront him, but you structure the movie to show that he is clearly lying.

Yes, and often he says that his interrogation techniques didn’t migrate to Afghanistan and Iraq. He reads the Haynes memo—it’s one of my favourite moments in the film—and he seems amazed. ‘That’s a pile of stuff,’ he says. He has to interrupt himself. It’s cluelessness—and I’m a fan of movies about the clueless—it’s cluelessness on an unprecedented level from someone so unbelievably powerful. He can say anything because I don’t think it matters to him.

Do you think he is afraid of being tried as a war criminal?

Well, clearly no. No one has ever been punished in America for war crimes. Why would he be afraid? McNamara actually came with me to the International Criminal Court, we showed The Fog of War to the ICC, and we answered questions. Rumsfeld I don’t believe could do that. First of all he doesn’t believe in the ICC, second of all he’d probably be arrested if he showed up in Europe. A friend of mine, Joshua Oppenheimer, just made a movie, The Act of Killing, about the genocide, politicide, whatever you want to call it, where the people were never punished. They were never held accountable; in fact, many of them are absolutely proud of what they’ve done. And I’ve heard people say, ‘Well how could such a thing happen? Well, I suppose it’s a Third World country. It really couldn’t have happened here.’ Of course, not only could it happen here, it has happened here.

When Rumsfeld describes Saddam Hussein becoming a caricature of himself in the end, were you drawing a parallel?

That was the second day of interviews. You know, I’ve heard people say to me, ‘Is he suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder? Is he a sociopath, is he a psychopath?’ I’ve always said that I prefer not to medicalize any of this, but there is a new medical syndrome that I’d like to put into some future version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and I call it ‘Irony Deficit Disorder.’ He said that Saddam, at the end, had become all pretend, and I think to myself, ‘Well surely he must realize that other people might think he’s talking about himself.’ So I’m looking at him, I’m looking at him for just some moment, but there’s nothing. Just nothing. Irony Deficit Disorder. His wife—who I really, really like—he wanted me to interview Joyce. I interviewed Joyce, I was happy to interview Joyce, it was a good interview, I knew I wasn’t going to use it in the film…Joyce talks to me for two hours, he’s sitting on a folding chair in the studio listening. Joyce goes back into the dressing room, he walks up to me and said, ‘It’s really nice to listen to someone who thinks before talking.’ So I think, surely he must realize that what he said could be interpreted by some other person, say myself, as about him. Nothing. It’s not there. What did Gertrude Stein say about Oakland? ‘There’s no there there.’ And I think that people get really angry about the film. They think somehow that my job is to show the cloven hoof. You know, you want to know what’s in the sleeve, and then somehow, suddenly, the cloven hoof appears. But what if there is just this emptiness, a lack of engagement? These ridiculous slogans, principles, rules, epithets, it’s Chinese fortune cookie philosophy. It’s just an amazing nightmare that this guy was in control of the Pentagon. He says nothing migrated from Guantanamo to Iraq and Afghanistan, so this question has come up again and again because I read the Schlesinger Report which says the exact opposite of what he just said, and he just looks at me, like a frog on a lily pad, and he said, ‘I’d agree with that.’ Well, what is my job? Is my job to say, ‘What do you mean, you agree with that? You just said the exact opposite.’ But I say nothing. We sit there and we look at each other and there’s this long pause. To me, it’s at the heart of this whole enterprise. There would be very little to gain by asking that question. It’s pretty clear that he is wrong. It’s also clear that he may not even care.

How long was the complete interview? How long did you spend with him?

33 hours. I also got the feeling that he would come back for more. That if I had really wanted to I could’ve interviewed Donald Rumsfeld for the rest of his and my life.

Do you think he was toying with you?

I don’t think he is playing a game. Unless that’s what he always does. Again, self-serving of me to say so, but this movie captures the real Rumsfeld, it’s just hard to reckon with. Hannah Arendt, who wrote about the banality of evil in Eichmann in Jerusalem, endlessly criticised that phrase but there’s a version that appears in a letter to the Jewish philosopher, Gershom Scholem, and Hannah Arendt says that the banality of evil is not the presence of something, it’s the absence of something you’d expect to see but just isn’t there. I was thinking the venality of evil, a guy who seems in the end to descend into a sea of gobbledy gook, definitions from the pentagon dictionary and other lies, crazy principles. ‘The absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.’ Well, that was popularised by your Astronomer Royal, Martin Rees, but it was used by him and Carl Sagan to speak about extraterrestrial intelligence. Here it’s about WMD in Iraq. If someone goes into Iraq, say a Hans Blix, and can’t find anything, that is evidence. That’s not the absence of evidence, that’s real evidence! I just have this picture of … George Bush was a recipient of a snowflake in which Rumsfeld says, ‘The absence of evidence isn’t the evidence of absence.’ I see Bush reading this thing, he’s trying to decide whether to go to war? I mean, I kept thinking, ‘We really are fucked.’ Just think about it for a minute. I say to you, ‘Better get ready. There are flying monkeys armed with thermonuclear weapons that are heading over the Thames right now as we speak. You have about three or four minutes to say goodbye.’ You say to me, ‘Wait a second, Mr. Morris, what evidence do you have for these flying monkeys with thermonuclear weapons?’ and I look at you like you’re a bunch of idiots, and I say, ‘Well, absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.’ People bought this, that’s what so nuts! He was the aluminum siding salesman for the war.

Did you challenge Rumsfeld about whether torture produced anything that saved America?

This is an interesting point, certainly about my role in all of this, that I should become involved in this question with Donald Rumsfeld, whether torture works. Do you think torture works? Say it does work, do you think it’s morally acceptable in a democracy such as ours? I have strong feelings about this subject but my desire to talk about it with Donald Rumsfeld is nil. What do you think he would say? Years ago I was a private investigator; I’ve made a whole number of films that could be seen as investigative in nature, certainly The Thin Blue Line, and my own belief is that you don’t find stuff out by torturing people. You find stuff out by listening to people. And do I believe that America is made a safer place through torture? No. I don’t. I think it’s a terrible, terrible black stain on our democracy. What amazes me is that Rumsfeld can’t engage it on any level: ‘Have you read the torture memos?’ ‘ No, why would I read the torture memos? I’m not a lawyer. I was prevented by the Justice Department…’ And then he does this amazing thing—this is, again, at the heart of this movie—he says, ‘Chalk that one up. Yeah, I really showed you what’s what, Mr. Morris.’ Maybe it is a game; it’s this feeling of maybe it’s wrestling all over again. At college he was almost an Olympic wrestler, maybe he’s pinned me to the mat. He’s famous for his use of the fireman’s carry, where he would pick someone up and throw them on the ground, and pin them. I think we all lost. I don’t think there’s any winning this game.

It was frustrating in that for two hours all we saw was Donald Rumsfeld evading…

I could have fought with him more, I could have pushed him more, I think that’s clearly true. People complain that’s it not like The Fog Of War, and of course it’s not like The Fog Of War. Different individual. I say, ‘You make a movie with the Secretary of Defense you have, not the Secretary of Defense you want to have.’ In The Fog of War there’s a kind of faux redemption. At least that individual is reflective, has a moral compass, is tortured by what he’s done and feels a need to give an account of it. Here Rumsfeld is not tortured by what he’s done. He’s proud of it; he’s completely happy with what he’s done. It probably would be more satisfying, I can’t disagree with you, if I had challenged him unendingly, but it’s my attempt to capture something about him, and I feel it’s successful. It may be truly unsatisfying as a movie, there’s something unsatisfying about the experience of interviewing him. Every single reporter who interviews me about this movie asks me, ‘Why did he agree to do this?’ as if I have some secret answer, which I do not. But I remind, them his answer to almost every single question that he’s asked is the answer that he gives at the end of this film when I explicitly ask him, ‘Sir, why are you talking to me, why are doing this?’ It’s a two-part answer: one is ‘That’s a vicious question,’ the other is, ‘I’ll be darned if I know.’ ‘Why did you invade Iraq?’ ‘I’ll be darned if I know.’ ‘Why did you do anything?’ It’s a movie about a singular inability to reflect. He’s the opposite of McNamara.

When Rumsfeld wasn’t on camera, was he in any way different?

Not at all. What you see is what you get. I have written a piece for the New York Times opinion pages that goes up next week on ‘The Philosophy of Donald Rumsfeld,’ such as it is; my attempt to deal with all of these slogans and epithets. What do I make of this whole experience? What would you have liked to see me say, ‘You’re full of shit,’ or ‘You’re lying,’ or ‘That’s clearly untrue,’ or ‘How can you say that! You should be ashamed of yourself?’

Was there anything you feel unsatisfied about, that you didn’t get? Like a confession?

No, I never go into these things looking for some kind of confession. I’m a filmmaker, I’m not a priest. I go into it wanting to learn something, wanting to listen. I mean, there was a horrible danger in this interview that he would just go into some spiel, and often he did. It would go on and on and on and on and on…I felt like I had pushed the button on a vending machine. This is very, very odd—the first day that I met him, when I came to Washington, I’m in his office and he invites me into the conference room. I’m there for most of the afternoon, to listen to him being interviewed—this is before I interviewed him—sitting next to him, in this conference room, listening to him being interviewed on speakerphone, from Fort Bliss. The book had just come out and the reporters all asked the same questions, and he gave the same answers, or if you like, the same non-answers to the same questions. Guess what questions they asked? They asked, ‘Do you feel the force that invaded Iraq was large enough? Did you feel that Saddam Hussein actually had WMD? Do you feel that adequate preparations were made for the aftermath of the invasion?’ Same questions, same answers. If I said that this is the most difficult interview I’ve ever done, it’s the unbelievable sense of frustration, a sense that there has to be something here, something more. How many people have said to me how brilliant Rumsfeld is? Often they cite the known known, the known unknown, the unknown unknown…many, many people said they find this brilliant. I don’t! Go back to the original press conference where he first brought these concepts out; I interviewed the three reporters who asked questions. One of them was the NBC Pentagon correspondent Jim Miklaszewski, and he said to Rumsfeld, ‘What evidence do you have that Saddam Hussein has WMD or is selling them to terrorist organizations, or providing them to terrorist organizations?’ And Rumsfeld answers, ‘Well, there’s the known known, the known unknown, the unknown unknown …’ And Miklaszewski interrupts and says, ‘But that’s not what I asked. I’m asking you, what evidence do you have that Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction?’ And this is at the heart of the problem. It’s not an evasion, that’s what’s the scary thing, he actually buys into this bullshit. And what is the issue? The issue is not the known known, the known unknown, the issue is separating fact from fiction, separating true belief from fantasy, telling us, what evidence do you have for this belief? And that was never there; what was there was a kind of philosophy that tells you that evidence isn’t worth anything. What does he say to Pam Hess? ‘I KNOW there are weapons of mass destruction.’ And in his head he thinks he knows. Even at the very end of the movie, when he can’t even get his own bullshit straight in his mind, he can’t decide whether the unknown known is about knowing more than we think we know or knowing less that we think we know. But isn’t the real issue—what separates us from the middle ages—that we think about what we believe, and we think, ‘What is the justification for that belief, what evidence do I have for that belief? So you may think he’s as smart as you want to think, and you may think that somehow he’s successfully evaded my questions, which, if they had been more penetrating, would have revealed something more. But his is a story about evasion to no purpose at all, evasion as a lifestyle, evasion as the heart of the matter, and it’s a powerful movie about that. Unsatisfying? Probably. Sorry.

COMMENTS