A.C.O.D.

Who said independent films had to look cheap?

Plot summary

Carter is a well-adjusted Adult Child of Divorce. So he thinks. When he discovers he was part of a divorce study as a child, it wreaks havoc on his family and forces him to face his chaotic past.

A.C.O.D. is one of those Sundance films—slick, sturdy, likeable (see last year’s Liberal Arts)—that forges no new paths or stretches no boundaries (except the career prospects of the director). Nothing adventurous, nothing experimental (see Upstream Colour, or last year’s The Oversimplication of Her Beauty; movies that expand the language of cinema and mess joyously with your head, which was the traditional realm of independent cinema pre-Sundance), except in the sense of making a picture that looks as good as the best of shiny Hollywood on a fraction of the budget. And there’s nothing wrong with that (ibid. Liberal Arts, or even Little Miss Sunshine).

Sundance has become so big and important that though it does highlight films that would never been anywhere else (see the careers of Darren Aronofsky and Shane Carruth), it is just as much a cauldron for traditional filmmakers seeking their breaks. A.C.O.D is not really indie, in the way that Clerks was indie. The filmmakers, including Zucherman and his co-writer Ben Karlin, have a lot of years, and awards, in the biz. They’re pretty much Hollywood insiders, working, between them, on Six Degrees, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, and Modern Family. And here, they’ve made it to the big screen. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

A.C.O.D. stands for Adult Child Of Divorce. I took this to be a satire on the wealthy, privileged, narcissistic need for the latest boutique stigma, a designer affliction, a self-help crutch (see Running from Crazy), yet another acronymic license for whiney, self-serving luxury victimhood (again, see Running from Crazy). I thought it was a joke. But was it? In a Q and A, Stu Zicherman seemed to talk…seriously. And audience members would introduce themselves as ‘also ACOD’, without smiling, like it was a 12 step meeting. ‘Together,’ Zicherman said, ‘we set out to write a script that would speak to Adult Children of Divorce everywhere.’ Americans are not normally known for humour this dry.

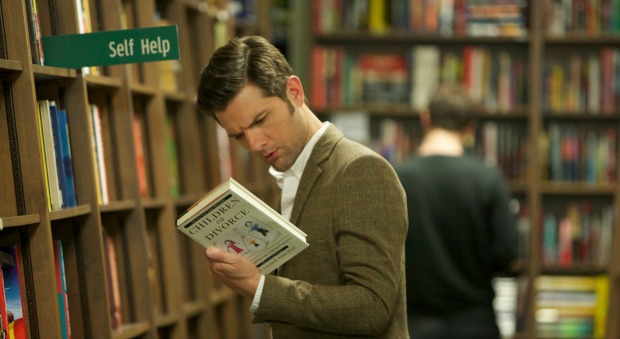

My advice would be to see the film, enjoy it, laugh out loud, and don’t go to any Q and As or read the director’s statement, because A.C.O.D is superbly plotted, as one would expect from network comedy writers, lovely to look at it, and delightfully acted. Carter (Adam Scott, Parks and Recreation) is an A.C.O.D., poor thing, charged with bringing together his parents for the wedding of half-brother, Trey (Clark Duke Hot Tub Time Machine). His parents, Hugh and Melissa (Richard Jenkins and Catherine O’Hara) are caustically alienated, bitter combatants in a scorched-earth divorce. But the Large Hadron Collider reaction that everyone expected by bringing them together doesn’t occur, and instead they actually…get along. Too well. What are solipsistic yuppies to do when people act outside the paradigmatic structure said yuppies have set up for them, and for the world? And when Carter finds out that he was in fact the subject of a study of children of divorce—and not merely going to therapy, as he’d been told—and was featured prominently in a book by a struggling academic (Dr. Judith, played by Jane Lynch), well, things get wacky in a heartfelt way.

The cast is superb, turgid with comic talent trained in improv (Jane Lynch from the films of Christopher Guest, Catherine O’Hara from SCTV, Amy Poehler from Saturday Night Live) and the inestimable John Bailey is the cinematographer (more in his James L. Brooks mode than his Paul Schrader mode). Who said independent films had to look cheap?

COMMENTS