Ten films to look out for from the BFI London Film Festival 2016

A superb array of films were offered up by the BFI London Film Festival this year: winners from the Cannes and Sundance film festivals, animation in all the categories and strands, new films by Paul Verhoeven, Oliver Assayas, Oliver Stone, Pablo Larrain, Werner Herzog, and the makers of Troll Hunters, and two documentaries about David Lynch. You could never go to any other films in the next year and be caught up for the Oscars. Here are ten to watch out for.

American Honey (Dir: Andrea Arnold)

What would Arnold, the poet laureate of uniquely British disenfranchisement, of the nuance of class and the rigour of the council estate, do with the open American road, and the unique disenfranchisement of Americans who nonetheless have endemic and inextinguishable optimism (delusional though it sometimes may be) at their core?

She would make one of the year’s great films and win the Jury prize at Cannes.

Elle (Dir: Paul Verhoeven)

A new Verhoeven! Starting back in the ‘70s, Verhoeven was one of the masters of world cinema, a kind of a glitzy Bergman; edgier, but important and serious. One day outside of a cinema I saw a poster for a film called Robocop, and immediately laughed because it seemed satirical, a joke title ridiculing the high-octane, quasi-fascist idiocy of the Reagan years (the years where the box office was led by Schwarzenegger, Van Damme, and Stallone). Then I saw the name of the director: Paul Verhoeven. That couldn’t be right. That name was already taken! You can’t use the name of the director who made the middle-ages drama Flesh + Blood, the low country Hitchcockian thriller The Fourth Man, the Oscar-nominated Turkish Delight (a tale of amour foudre which went on to be named ‘The Dutch Film of the Century’). But it was him. It was like, say, seeing the announcement of Bertolucci directing, well, a film called Robocop. And that was followed by Starship Troopers and, of course, Showgirls, a film that was so ludicrously bad that I maintain it was done on purpose, and in fifty years the world will catch up to its brilliance and hail me as a great visionary. Then a couple of years ago, Verhoeven made Black Book, which looked and felt like a Verhoeven movie of old. It was complex, it was grown up. Verhoeven claimed—and this may not even be a quote; I may have only dreamed that he said this, but I still like to think he did—that he had been lost for 20 years in Hollywood, like in an alien abduction, and had no memory of the atrocities done by him and to him, but was back now, released from the evil mothership. Anyway, he’s returned, as he once was, and his new film, Elle, has Isabelle Huppert! It also has high-end revenge, suspense, strong women on the rampage—this is Verhoevenland in full bloom.

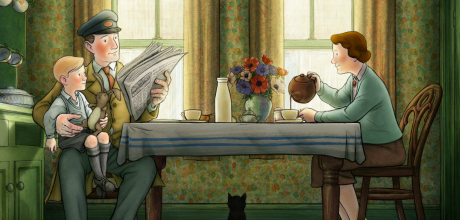

Ethel and Ernest (Dir: Roger Mainwood)

A friend of mine, Mhairi, who works at the company that did the post-production for this, said that Ethel and Ernest, a hand-drawn animation about a quiet, ordinary couple getting by in the war (voiced by Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn), may not be the most dramatically explosive film, but it is quiet and beautiful and melancholy and funny and gentle. She says that, doing the post work, she’s seen it at least 10 times, and would happily see it again. A movie that you’d see for the eleventh time! You heard it here first.

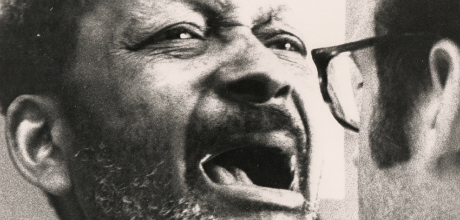

Hospital (Dir: Frederick Wiseman)

From the excellent BFI archives, this is a black and white documentary from 1969, made by one the leaders of the Cinema Verite brotherhood. Wiseman’s films scathe you, challenge you, take you to places nice people shouldn’t go, make you experience lives of people who’ve been forgotten. But you won’t forget. In Hospital, Wiseman goes deep into New York’s Metropolitan, giving us the pain, the terror, the hope, the compassion, the tedium, the humor, the anguish of raw New York (before Disney; a city known for its murders, its drugs, its garbage strikes). Want to change your life? That’s perhaps a warning as well as an invitation.

Nocturnal Animals (Dir: Tom Ford)

Ford brought, as one would expect, a controlled and disciplined eye to the aesthetics of A Single Man, but, perhaps less expected from a man who frets over the piping of a power-blouse (or so I gather), a subtlety and perspicuity of unsounded emotional turmoil to that aesthetic. He displayed a visual language that told the story, with restraint, with an innate skill that rivals that of other more experienced (well, less first time) directors. Nocturnal Animals looks to be full of secrets and betrayals, regrets and revenge, a noir-tinged soured love song set in the rarefied world of publishing and L.A art galleries, with the excellent Amy Adams, who won the Oscar, and Jake Gyllenhaal, who won the genetic lottery.

Chi-Raq (Dir: Spike Lee)

Where’d the joints go? There hasn’t been a Spike Lee joint in years! Or none that anyone noticed. They used to be a regular, those joints, and anticipated as Coen Brothers’ films. Lee, like the Coens, was at the forefront of the American Indie scene before there was a scene, and is not only a visceral and buoyant filmmaker, he was also one of the rare, rare black voices in the film zeitgeist. And he never compromised. Chi-Raq, a conflation of Chicago and Iraq, takes on the atrocity of the gun violence in America’s black neighborhoods, notably Chicago, but in Lee’s own galvanizing way. A timely social indictment, it is also an adaptation of Lysistrata, a comedy by Aristophanes, written in 411 B.C. And for the Greek chorus? A pimped-out (is that racist? I think Lee would welcome my confusion) Samuel L. Jackson. With songs! And shootings! And, one hopes, the searing cotton candy verve and tension of his heyday, Do The Right Thing.

La La Land (Dir: Damien Chazelle)

Whiplash, the feature, made me worried. Was is it just going to be a bloating of the superb, taut short? No, it was not. It was a masterwork. And for his sophomore film, Chazelle has decided to do an RKO-style musical. Alas, the word ‘sophomore’ is often followed by the word ‘jinx’. And sadly, it’s often apt. A young filmmaker works for years in oblivion to bring his first feature into the world, it gets critical acclaim, and he is given more money and freedom than he knows what to do with. Then he misjudges precipitously because no one around him is saying no. Will La La Land follow in the footsteps of Kevin Smith, who gave us Mallrats after the cause célèbre that became an indie template, Clerks? (He got back on track, luckily, with Chasing Amy). Or will it be a revelation, like, ‘We thought he had promise, but, shit, he’s a fucking genius’? Like Todd Solandz’s Happiness after his Sundance success, Welcome to the Dollhouse. La La Land is perhaps risky, taking on the genre with the greatest cheese potential, but we should not fret; Chazelle, as a filmmaker, is the Fred Astaire of dodging cheese. Whiplash, for example, was no Glee. It was, in fact, as devastating as the first 20 minutes of Saving Private Ryan. La La Land is a singing love story, but without the naivete; freeway traffic jams instead of marble staircases. It captures the inextinguishable allure of Hollywood heritage and Hollywood musicals, the love affair/murderous annoyance we have with L.A.; you love it despite its shallowness, its frustrations, it’s mediocrity, because L.A. isn’t just a behemothic entity, it’s also made up of people with dreams and good intentions.

Toni Erdmann (Dir: Maren Ade)

It sounds kind of awful. A fright wig and gnarly plastic teeth—now that’s comedy! And the Germans, well, I mean, are they known for their sense of humour? But the honesty, spontaneity, the gentle humanness of the performances made the Cannes audiences pee their pants in delight. It’s about a father trying to reinvigorate his daughter, who’s stuck in malaise, by being wacky. He takes on the guise of a stranger called Toni Erdmann to jolt her back into life. The miracle of the movie is that there is no unallayed wackiness, but gentle honesty, a real sadness behind the eyes. This could be one of those films that come by very rarely.

Mascots (Dir: Christopher Guest)

He’s never done anything wrong before, how can this not be great? This is about competitive mascots, those unnecessary irritations and the most ridiculous thing about any public event. They’re brand logos, basically, come to shoddy life by hot, sad people in mangy costumes. It’s always cringey knowing it’s an adult who is out of work and desperate in a moth-eaten plush sarcophagus who has to breathe out through the eyeholes. Why are they even there? It seems mainly to create a sense of community: a community of shared, unanimous loathing, and sometimes they fall over or get hit and we love to see that more than we do the hometown team winning. So it’s a perfect milieu for Guest, whose films dissect American everyday absurdity by focusing on one of it’s more peculiar niche obsessions. But the films are never mockery—they work because the cast (the magnificent ensemble are mostly back—sadly, no Catherine O’Hara or Michael McKean or Eugene Levy, but everyone else returns) never wink. They’ve played various obsessives (in dog shows, in the folk music scene, in the race to the Oscars) through the years with earnest evangelic belief.

Manchester by the Sea (Dir: Kenneth Lonergan) and Paterson (Dir: Jim Jarmusch)

I’m sneaking two in here because I’m a dirty cheater.

A friend of mine once told me that he hated what he called ‘squeaky screen door movies’, films about the strata—geographical, economic, cultural—of America that is far from cosmopolitan ease. Small, ordinary lives, people with problems and preoccupations that were distinctly not Hollywood high concept, and who always lived in shitty neighborhoods in houses that had a squeaky screen door. I, on the other hand, love them. And these two films look like they’re going to have plenty of squeaky screen doors opening onto porches that need paint jobs, in, respectively, New Jersey (Paterson) and the neighbourhoods in Massachusetts that aren’t Cambridge (Manchester by the Sea).

Jim Jarmusch uncompromises like no other filmmaker. He knows the reticent language, the existential malaise and exquisite hope, of people who’ve been marginalised. These are people who sometimes struggle, sometimes scam, just to get by. In Paterson, Adam Driver is a bus driver and Golshifteh Farahani is his wife. They live in a small house. He writes poetry, she bakes cupcakes. That may be all there is to it, and it sounds awesome. Plus the film won at the Cannes this year—the Palm Dog Award. For Nellie the dog.

Lonergan, in Manchester by the Sea, has Casey Affleck and Michelle Williams struggling to come to terms with their shattered family and make sense of it when it is suddenly redefined. Casey Affleck is an actor who wears his soul on the outside, and according to the programme, gives a ‘an indelible, career-defining performance.’ I’ve only seen a clip, featuring Affleck, and I could just watch that on a loop and be satisfied, so the other 136 minutes will be just gravy. And Adam Driver, also according to the programme, ‘hits a career high,’ which is something for an actor who is not only an indie demi-god but also the new Darth in Star Wars. Both of these films are from Bernie Sanders’ America, where the special effects are the performances, and where the budget went into the writing.

COMMENTS