Making Contact

Exploring book adaptations and the young woman adventurer in contemporary Hollywood Science-Fiction.

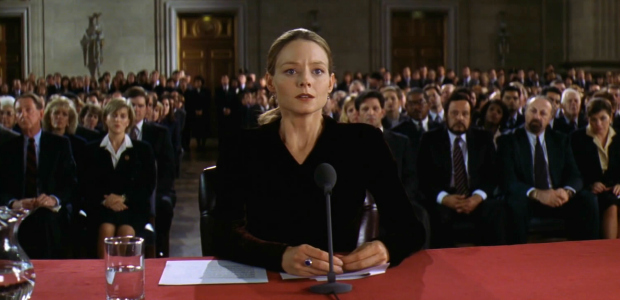

In the penultimate scene of Robert Zemeckis’s 1997 film Contact, the protagonist Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) talks to a group of children about the planned enlargement of the vast array of radio telescopes that can be seen in the New Mexico desert behind her. In response to Ellie’s statement that new telescopes will allow scientists to reach farther into space than ever before, one of the boys asks: ‘Are there other people out there in the universe?’ As the film’s story up to this point has shown, Ellie has, in fact, already received a message from an alien civilisation and gone on an amazing trip to another world, where she encountered an extraterrestrial being. Yet upon her return, her testimony was discounted as delusional by government officials wanting to hide the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence from the public. Having no proof for her story and being a skeptical scientist herself, Ellie appears to have accepted that her story is indeed unbelievable. So she does not tell it to the boy. Instead she says: ‘Good question. What do you think?’ The boy shrugs his shoulder: ‘I don’t know.’ Ellie is pleased: ‘That’s a good answer. A skeptic, eh?’ Addressing all of the children, she then pleads: ‘The most important thing is that you all keep looking for your own answers.’

The little boy’s curiosity and skepticism echo her own, both now and in the past when she herself was a child wondering about life in other places, trying to make contact with it through her CB radio, which she is shown doing at the very beginning of the film. In the same way that, in the course of the film, Ellie has grown up to be an astronomer, she now sees the children she talks to as potential future scientists, forever looking for their own answers. Ellie confides in them: ‘I tell you one thing about the universe, though: The universe is a pretty big place…. So if it’s just us, it seems like an awful waste of space.’ Putting a construction helmet on a little girl’s head, she concludes with the last word spoken in the film: ‘Right?’ It is a question, but the way it is put suggests that for Ellie it is merely common sense to assume that there has to be something out there to fill the void.

It is this suggestion and a call for curious, yet skeptical inquiry which Ellie passes on to the children, not the fantastic experience she has had. Her biggest adventure may be over without her being able to communicate it, yet here she is, telling children – and in particular a little girl – to embark on a journey of intellectual discovery similar to the one that eventually took her across the universe. Rather than feeling embittered about the fact that her report about this amazing adventure has been discredited, she appears hopeful that one day, one of these children, or in turn one of their children, will be able to repeat her experience. And by addressing her last comments to a girl, she perhaps also expresses her hope that in future it will again be a female adventurer who makes contact.

The penultimate scene of Contact, then, concerns the relay of insights, values and attitudes from one generation to the next, and, more specifically, from a woman to a little girl. At the same time, coming so close to the end of the film, the scene serves as a kind of relay between the fictional world of the film’s story and the reality of the people in front of the screen. When Ellie talks to the children, she also addresses the film’s audience, who, in the preceding scene, have been presented with evidence confirming Ellie’s testimony about her journey, but who may still be unsure about the implications of the fantastic story the film has told. As an audience of Ellie’s final comments, we are invited to be like the children on screen, skeptical, yet curious and also confident that there has to be something out there, which we will find if only we keep looking.

The very last scene of the film shows Ellie alone squatting at the top of a canyon at dusk, picking up some earth and examining the patterns formed by glittering tiny stones on her hand. These stones look a bit like the stars in the night sky above her, and this night sky, which is the film’s final image, in turn is like a darkened screen. This suggests that the sky which Ellie has been studying all through the film is not distant and alien, but like the palm of her own hand, and also like the screen which we have been examining so intently for the preceding two and a half hours. And what Ellie has experienced as a result of her studies – the trip to another world -, is also an encounter with herself, in the same way that the film for us is both a larger-than-life event and a very personal experience. Ellie comes out of this experience as a more rounded person and a teacher, and also as someone who continues to examine the skies and herself. We are invited to do the same, although perhaps it is first and foremost the screen we are asked to look at, the cinema we are asked to return to, for further experiences and insights.

In this article, I want to demonstrate that, like many contemporary Hollywood films, Contact combines a realistic psychological drama with a fantastic generic story, and at the same time, it is a film about the cinema itself. Furthermore, like numerous other contemporary films it is based on a novel, a fact the viewer is reminded of with the dedication ‘For Carl’ which is superimposed on the final image of the night sky, reminding us of the author Carl Sagan, whose novel the film is based upon, and who died a few months before the film’s release. I will use Sagan’s 1985 novel Contact as a key to understanding the film and its place both within contemporary Hollywood cinema and within a long tradition of girl-adventurer stories.

This article continues my exploration of important trends in, and the cultural and political resonances of, contemporary Science Fiction cinema, which I embarked upon with my last essay for Pure Movies.[1] Once again I am writing about a film that has profoundly affected me.[2] I begin with a discussion of the similarities and differences between novel and film.

The book was better than the movie. For one thing, there was a lot more in it

This quotation is taken from the novel, where it relates to the young Ellie’s response to an illustrated version of Pinocchio.[3] Growing up in the 1950s, Ellie seems to have seen the 1940 Disney film first, and as a highly intelligent and critical child, she finds the printed text so much richer than the movie. Indeed, Hollywood’s literary adaptations are often characterised by the simplification of the complex stories and storytelling strategies of their sources: dropping or merging minor storylines and characters, reducing the narrator’s commentary on the characters’ thoughts and actions, narrowing the scope of the narrator’s moral, historical and philosophical reflections. There are various reasons for such simplification of the source material. First of all, there is the time factor. While even a longish Hollywood film such as Contact hardly ever lasts much longer than two hours, it takes many more hours to read the hundreds of pages of a medium-length novel.[4] Apart from having less time to tell the story, Hollywood films also rarely use extensive voiceover narration and are thus unable to reproduce the narrator’s discourse in a novel. Finally, Hollywood films tend to focus on the psychology and agency of individual protagonists and their antagonists, rather than on the interaction and development of larger groups of people. All of this certainly applies to the film version of Contact.

Before discussing the changes made to the novel, however, it has to be emphasised that in its general outline the film does reproduce its story. Precocious Ellie Arroway, whose father dies when she is still a child, grows up to be an astronomer who is passionately dedicated to the radio search for extraterrestrial intelligence, first at an observatory in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, then in New Mexico. During her time in New Mexico, a signal from the star Vega is received, which she helps decoding. It contains instructions for a machine that appears to be designed to transport people. Under American leadership, governments and companies from all over the world collaborate to build the machine, which is, however, destroyed in a terrorist attack that also kills Ellie’s former teacher and great rival David Drumlin. Using another machine which has secretly been built in Japan, Ellie is then placed in the passenger pod and the device is activated. What she experiences is a journey to another world where extraterrestrials present themselves to her in the shape of her dead father, telling her about the diversity of life forms in the universe and that eventually humankind will participate in intergalactic exchange. For now, however, Ellie has to return to Earth, where her report is met with disbelief, because, from what observers could see, nothing has happened at all. The passenger pod never disappeared; it fell directly into the water. Consequently, Ellie’s testimony is discredited, yet she is enriched by the memory of her great adventure.

While this basic story is shared by novel and film, the cast of characters has been reduced in the movie. For example, a friendly, international network of fellow scientists that Ellie is part of has been dropped, and instead she is partnered with blind radio astronomer Kent Clark, who supports her work throughout most of the film but does not even appear in the novel. In addition to picking up and analysing radio signals, in the film Ellie and Kent listen to those signals, and it is them rather than computers making the most important discoveries. Furthermore, whereas in the novel five scientists make the journey across the universe, in the film it is only Ellie. Thus, the film’s narrative is primarily moved along by Ellie’s actions (as well as Kent’s), and it is almost exclusively her responses to events that are being explored. The novel, on the other hand, contains long sections in which the narrator outlines the biographies and experiences of Ellie’s fellow scientists, explores the impact of the reception of the extraterrestrial message on all of humankind, and describes the origins of the radio message itself and its journey across the universe towards Earth. The film does not contain such extensive digressions from Ellie’s storyline, yet it does manage to give a sense of the wider impact of the extraterrestrial message by featuring numerous clips from television programmes, ranging from news to talk shows, in which international developments are briefly sketched and various commentators (most of them real TV personalities such as Jay Leno) present their own responses.

One such commentator is Palmer Joss, a high profile religious figure, critic of science and presidential adviser, whose role is made very personal in the film by turning him into Ellie’s love interest (a function fulfilled in the novel by government bureaucrat Kenneth der Heer, who does not appear in the film at all). Furthermore, the film sharpens the conflict between Ellie and Drumlin, turning the latter into a proper antagonist, and it also shows the ‘helper’ figure, the superrich and eccentric inventor and entrepreneur Sol Hadden, taking a much more personal interest in Ellie than he does in the novel, almost like an all-seeing, all-knowing, all-powerful father figure who makes sure that everything turns out alright for her.[5]

In evaluating such changes, many critics would probably concur with Ellie’s judgment that the simplification of source material in film adaptations inevitably means that a novel is better than the film that is being made from it. Common as this judgment may be, it is unlikely to have been shared by author Carl Sagan, who did, in fact, first develop the story of Contact, together with his wife Ann Druyan, in 1980/81 as a treatment for a movie.[6] The film’s credits list him and Druyan as co-producers, which indicates that Sagan had substantial involvement in the making of the film and probably approved of the final shape it took. In any case, the ending of the film does preserve what Sagan describes as the single most important objective of the book, which is to inform people about the scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), and to solicit interest in, and support for, this search. In his ‘Author’s Note’ at the end of the book, Sagan thanks ‘the world SETI community – a small band of scientists from all over our small planet, working together, sometimes in the face of daunting obstacles, to listen for a signal from the skies.’ And he states: ‘My fondest hope for this book is that it will be made obsolete by the pace of real scientific discovery.’[7]

The author’s note reflects Sagan’s dual position as, on the one hand, a practicising scientist and promoter of science, and, on the other hand, an entertaining storyteller. This is reinforced by the biographical sketch which concludes my paperback edition: Sagan is described as a ‘distinguished astronomer’, who holds a professorship at Cornell University, ‘has been deeply involved in spacecraft exploration of the planets and in the radio search for extraterrestrial intelligence’, and has won ‘numerous awards’ for his scientific work. At the same time he is said to be ‘the most widely read scientist in the world today’, whose 1980 book Cosmos is ‘the best-selling science book ever published in the English language’, whose 1978 book The Dragons of Eden won the Pulitzer price, and whose previous novel Comet (co-written with Ann Druyan) had been a bestseller.[8] Thus, the novel Contact is presented less as a purely fictional and merely entertaining tale, than as an extension of the author’s actual research and of his factual publications, which have made him, in Constance Penley’s words, ‘America’s most famous science popularizer’.[9]

In many ways, at the end of the film, Ellie Arroway takes on precisely this role of the high profile populariser of science, with respect both to the children in the film and to cinema audiences all over the world. It is certainly unusual that in the novel, and even more emphatically in the film, it is a woman who is presented as the mouthpiece for the male writer’s message about the importance of scientific inquiry. And it is even more unusual that it is a woman who is here placed at the centre of a $90 million Science Ficton movie. In the following two sections, I am going to explore this anomalous position of Ellie Arroway/Jodie Foster by relating Contact to a range of filmic and literary models.

Still waiting for E.T. to call?

These are the words with which presidential Science Adviser David Drumlin greets Ellie in the film when he visits her at the observatory in Arecibo, intent on closing down her SETI project, because for him extraterrestrial intelligence is merely a fantasy, just like the Steven Spielberg movie he is referring to. However, rather than being pure fantasy, Spielberg’s film carefully relates the appearance of E.T. in 10-year-old Elliott’s life to the disappearance of his father, who has recently separated from Elliott’s mother, an event which she and her children have great difficulties to come to terms with; indeed, the family seems on the verge of disintegrating altogether. In this situation, the extraterrestrial visitor comes to stand in for the absent father, helping Elliott to learn to accept his loss, and helping the family to grow into a unit again (which remains fatherless, however). The Science Fiction story thus works to play out and resolve the realistic familial drama at the heart of the film. As I have argued elsewhere, E.T. (the top grossing film at the US box office in 1982) is a typical example of the most successful production trend in Hollywood cinema since the late 1970s – what I call family-adventure movies.[10] Like E.T., most of the top grossing movies since 1977, such as Star Wars (no. 1 in 1977), Jurassic Park (no. 1 in 1993) and The Lion King (no. 2 in 1994), have appealed to family audiences by combining more or less fantastic, generic storylines and spectacular action sequences with a deeply felt emotional concern for familial or quasi-familial relationships, mostly focusing on the relationship between young males and their dead, alienated or incompetent fathers.

With his Back to the Future trilogy (no. 1 in 1985, no. 6 in 1989, no. 11 in 1990) and with Forrest Gump (no. 1 in 1994), Contact’s director Robert Zemeckis became, next to Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, the most successful representative of this production trend. It is therefore no surprise to find that the film version of Contact, much more so than the novel, revolves around Ellie’s relationship with her father. When she is a little girl, he encourages her scientific curiosity and introduces her to amateur radio and astronomy; and when he dies, 9-year-old Ellie sits down at her radio and calls out into the void: ‘Dad, this is Ellie. Come back.’ This wish implicitly underpins her search for extraterrestrial intelligence as an adult; she cannot live without the belief that humankind, and she herself, are not all alone in the universe; there has to be more than just a void. Thus it is highly appropriate that when she receives a call from outerspace, it contains the instructions for a machine which transports her to another world where she encounters her father. Of course, Ellie realises that her father has not arisen from the dead, and that what she sees is only the guise chosen by the extraterrestrials to present themselves to her. Still, the encounter does seem to heal an emotional wound, allowing her, after her return, to relate more closely to other people (which she had difficulties with before, out of a fear of further loss). When Ellie, in the film’s penultimate scene, tells the children that an empty universe would be ‘an awful waste of space’, she repeats a sentence her father said to her at the very beginning of the film. What she is really saying here, at an emotional level, is: In the face of our own mortality and that of our loved ones, we have to believe that there is more to life than our terrestrial existence.

While Contact is not addressed to a family audience, it does replicate the thematic concerns and narrational strategies of family-adventure movies. However, it differs from most other examples of this trend by focusing on a woman rather than a young male. In doing so, Contact follows another production trend in 80s and 90s Hollywood cinema, namely action-adventure and Science Fiction films which aim to overcome the traditional resistance of female audiences to these genres by placing a female character close to the centre or at the very centre of their narratives.[11] Again, as with E.T. and family-adventure movies, a reference to this production trend can be found in the film itself. When Drumlin has withdrawn government funding from Ellie’s work at Arecibo, she and Kent are forced to look for other sources of finance. Ellie tells Kent to go after ‘Hollywood money’: After all, ‘they’ve been making money off aliens for years’. Aliens is the title of James Cameron’s 1986 Sci-Fi sequel (the seventh highest grossing film of the year), which revolved around the efforts of its heroine (Ripley) to deal with the traumatic memories of her past encounters with an alien creature (in Ridley Scott’s film Alien, no. 5 in 1979), and with her journey across the universe for another showdown with the alien brood. Similarly, Cameron’s other major Sci-Fi hit, Terminator 2 (no. 1 in 1991), centres to a large extent on the thoughts, feelings and actions of its female protagonist Sarah Connor. And the highly successful science thriller Twister (no. 2 in 1996) starts, much like Contact, with the traumatic childhood experiences that motivate the heroine’s later pursuit of tornadoes; as a girl, Jo Wilder sees her father being sucked into a tornado with the result that she spends the rest of her life chasing twisters.

Thus, by the time Contact was made, Hollywood had already established successful precedents for making films about women, technology, the encounter with alien entities and the pursuit of knowledge. It is worth pointing out here that, before Contact, Jodie Foster’s biggest hit had been The Silence of the Lambs (no. 4 in 1991), the story of a young woman, who, as a little girl, has lost her father and as an adult tries to emulate him by working in law enforcement; her job is the pursuit of knowledge about crimes, and in the course of carrying out her duties she has to confront two alien monsters (serial killers Jame Gumb and Hannibal Lecter) as well as two substitute fathers (her boss Jack Crawford and Hannibal Lecter who is both a monster and a mentor). What all of these films have in common is their concern with female subjectivity, notably past traumas and formative childhood experiences, with a special emphasis on familial and quasi-familial relationships, which echoes the concerns of the family-adventure movies discussed above. Yet, where family-adventure movies deal with young men and their fathers, these female-centered action-adventure, Science Fiction and crime films focus on girls and their fathers, or mothers and their biological or adopted children: Ripley and her adopted daughter Newt in Aliens, Sarah Connor and her son John in Terminator 2, Clarice Starling and her dead father in The Silence of the Lambs, Jo Wilder and her dead father in Twister, as well as Ellie Arroway and her dead father in Contact.

It is important to note that almost all of these films draw heavily on classic stories which resonate powerfully across Western culture. The opening sequence of Aliens reworks the conclusion of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ – the princess being woken up after a long sleep -, except in the film, from this point onwards, the princess is doing the rescuing. Terminator 2 is retelling the story of the Holy Mary; like her, Sarah Connor has gotten pregnant under mysterious circumstances with the future saviour of mankind, but in a feminist twist to the biblical story she decides to save the world herself. Twister replays the opening of the film The Wizard of Oz (1939), complete with a dog keeping the little girl company during the storm; except here it is the father who is taken away by the tornado, not the girl. In a way, what Jo does during the remainder of the film is to try to reclaim her rightful place at the centre of the storm. Finally, Contact also draws on The Wizard of Oz as well as other stories about girl-adventurers, a connection which is made explicit both in the novel and in the film.

Off to see the Wizard

Shortly before Ellie goes on her big trip across the universe, the novel’s narrator comments on her state of mind: ‘Her romanticism had been a driving force in her life and a fount of delights. Advocate and practitioner of romance, she was off to see the wizard.’[12] The narrator also describes her as ‘a wonder junkie’; and confronted with the marvels of the universe, Ellie sees herself as ‘Dorothy catching her first glimpse of the vaulted spires of the Emerald City of Oz.’[13] Frank L. Baum’s classic children’s novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (first published in 1900) as well as the 1939 film are thus presented as a source of inspiration for Ellie, and Dorothy as her role model. Contact also references two other classic books which tell versions of the same story of a girl who is taken away from her domestic surroundings into another world where she courageously lives through numerous adventures before she manages to return home, namely Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (first published as a novel in 1911). When Ellie listens to a fellow scientist talking about extraterrestrial life, the novel’s narrator comments that for her ‘it was like entering Wonderland or the Emerald City.’[14] And at a critical point during her trip across space, Ellie worries that she and her fellow travellers could ‘find themselves stuck fast in this never-neverland.’[15] While the film is much less explicit in its references to these girl-adventurer stories than the novel (the only direct reference is a balloon with the word Oz imprinted on it in the background of one scene), it does replicate much of their imagery as well as their basic structure: a ‘normal’ earthly existence is established, then the female protagonist is ‘magically’ transported to another world, from which she returns at the very end.

The real excitement and appeal of all of these stories arise from the experiences she has during her trip, and the stories’ endings have to address the question of how their protagonists can return to their restricted everyday existence after they have had a taste of adventures which are usually reserved for males. How will they be able to live on with the memory of their big adventure? They could choose to forget it so as to be better able to accept their limited lives, or they could try to go on another adventure – as Dorothy does in the many sequels to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (unlike the film version, where the trip is just a dream, in the novel Oz is a real place). The solution presented in the other three texts, however, is a different one: the female protagonist holds on to the memory of her journey and tries to convey a sense of adventure to the next generation of little girls. At the beginning of this article, I emphasised that Ellie Arroway singles out a girl for her final comments in the film, which are in effect a call to adventure. I now want to conclude by looking at the endings of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Peter Pan.

First, here are the thoughts of Alice’s big sister about the dream that Alice has just awoken from: ‘Lastly she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.’[16]

Finally, here is the equally bittersweet ending of Peter Pan, in which the eternal boy returns after many years to Wendy’s house to take her away to Neverland again. Yet Wendy has grown up and is no longer able to fly. However, she wonders whether she could allow her little daughter Jane to join Peter: ‘Of course in the end Wendy let them fly away together. Our last glimpse of her shows her at the window, watching them receding into the sky until they were as small as stars. As you look at Wendy you may see her hair becoming white, and her figure little again, for all this happened long ago. Jane is now a common grown-up, with a daughter called Margaret; and every spring-cleaning time, except when he forgets, Peter comes for Margaret and takes her to Neverland, where she tells him stories about himself, to which he listens eagerly. When Margaret grows up she will have a daughter, who is to be Peter’s mother in turn; and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.’[17]

Conclusion

Since the mid-19th century, the same story about a girl’s extraordinary journey to another world has been passed on from one generation of women to the next: from Alice to her daughter, from Wendy to Jane to Margaret and Margaret’s daughter. While the novels were written by men, their narrators present themselves as mouthpieces for the girl-adventurers at the centre of the stories, allowing their experiences to be communicated to a wide audience. With Contact, Carl Sagan and Robert Zemeckis skillfully insert themselves into this storytelling tradition, presenting Ellie Arroway as a descendant of earlier girl-adventurers. At the end of the film, Ellie functions, just like the grown-up Alice and Wendy, as a maternal figure passing on her sense of adventure to another generation of little girls. While she is shown to have derived her curiosity and courage from her father, whose death she is coming to terms with through her adventure, the very beginning of the film hints at a deeper motivation, which relates Ellie’s exploration of the skies to her mother who died during her birth. Ellie is first shown as a little girl at her CB radio, calling out into the ether and making contact with a radio amateur in Florida. That same night, she asks her father whether she will be able to reach even more distant places, like the moon and Saturn. Then, after a pause, she asks: ‘Dad, could we talk to mom?’ So it is in fact her mother whose death motivates her attempt to reach out into the skies, and who thus is the inspiration for all her later adventures.

[1] https://www.puremovies.co.uk/columns/avatar-environmental-politics-and-worldwide-success/

[2] Indeed I have written about Contact before. See Peter Krämer, ‘”Want to take a ride?”: Reflections on the Blockbuster Experience in Contact (1997)’, Movie Blockbusters, ed. Julian Stringer, London: Routledge, 2003, pp. 128-40.

[3] Carl Sagan, Contact, London: Orbit, 1997, p. 16.

[4] Contact lasts 150 minutes in the cinema, and my paperback edition of the novel has 431 pages.

[5] Another significant modification is that Ellie’s birthdate is changed from the late 1940s to 1964, presumably so as to bring her age in line with the age of the actress who plays her. Furthermore, the film is mainly set at the time of its release in 1997 and during the following year or so, whereas in the novel the journey across the universe takes place on the last day of the millenium on 31 December 1999.

[6] Carl Sagan, ‘Author’s Note’, in Sagan, Contact, p. 431.

[7] Ibid., p. 430.

[8] Ibid., p. 432.

[9] Constance Penley, NASA/TREK:Popular Science and Sex in America, London: Verso, 1997, p. 5. This statement is, in fact, the beginning of Penley’s sustained attack on Sagan’s views on science and his rejection of what Penley calls ‘popular science’, exemplified by fans’ interest in the scientific implications of Star Trek; ibid., pp. 5-9.

[10] Peter Krämer, ‘Would You Take Your Child to See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family-Adventure Movie’, Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, ed. Steve Neale and Murray Smith, London: Routledge, 1998, pp. 294-311. Rankings in the annual US box office charts are taken from http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/.

[11] Cp. Peter Krämer, ‘A Powerful Cinema-going Force? Hollywood and Female Audiences since the 1960s’, Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences: Cultural Identity and the Movies, ed. Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby, London: BFI, 1999, pp. 98-112; and Peter Krämer, ‘Women First: Titanic (1997), Action-Adventure Films and Hollywood’s Female Audience’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol. 18, no. 4 (October 1998), pp. 599-618.

[12] Sagan, Contact, p. 323.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., p. 37.

[15] Ibid., p. 330.

[16] Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, Ware: Wordsworth Classics, 1992, p. 103. Emphasis in the original.

[17] J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan, London: Penguin Popular Classics, 1995, pp. 184-5.

COMMENTS